A sweaty trek to the summit of Angerkogel (Northeastern Kalkalpen, Totes Gebirge, Styria)

Patrick Schwager & Christian Berg

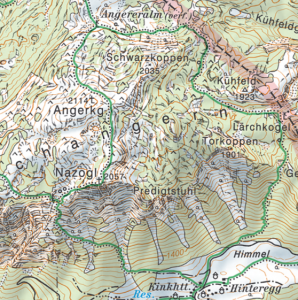

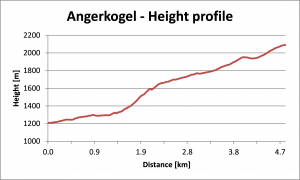

19th August 2016, 8:30 at the car park at Angeralm in the north of Liezen. It is the fourth day of our upper Styria-trip and we meet our colleague Dietmar who is working for his Master’s thesis at mount Angerkogel. He will show us some remote places where we will hopefully find special species from our target lists, not least Crepis terglouensis, which Christian and I have been looking for since the start of our collaboration with the Millennium Seed Bank Partnership in 2013. The way is long, nearly 5 kilometers, as we did not choose the direct way over mount Nazogl which we can see from the car park, as the longer way promises a good yield of seed collections.

Our way to the summit leads us through the pastures of Hinteregger Alm and then the montane spruce forest belt. As with most of the pastures in this region of Styria the Hinteregger Alm was created 800 to 1000 years ago. This mountain pasture is located at the foot of the Hochanger massive and is used as Niederalm (alpine pasture used in spring and autumn). The area is divided into three terraces and extends in altitude from 1150 to 1350 m.

From the start we could see the first individuals of Arabis ciliata, a species from rocky, dry grassland. We will find more of it up on the plateau. The forest part is the steepest part of the way, but luckily it is also the shortest part. In such habitats the taxonomically controversial Euphorbia austriaca grows and we could collect a substantial amount of seeds from this species on the way upslope. At lower altitudes, we find the similar Euphorbia verrucosa too.

Already on the ascent, white limestone cliffs (dolomite) can be seen which are characteristic for the karst landscape in this part of the north eastern Alps (Totes Gebirge). On these rocks, now and then Carex brachystachys hangs down in loose horst in cooler, moist areas, but unfortunately there were not enough individuals for a conservation seed collection.

In this alpine grassland between the calcareous rocks we began to collect Carex ferruginea and Achillea clusiana. We have also seen Festuca norica for the first time, but had to confirm its identification when we returned from the field. If you look carefully you can also find megalodonts, a group of shells from the Triassic, that look like hoof prints on the limestone rocks.

As we reach the plateau the spruce forest is gradually replaced by a mosaic of limestone rocks, alpine meadows and Pinus mugo shrubs.The karst geology of the mountains of the eastern part of the calcareous Alps results in summits that are typically plateaus. In the past the plateau at Angeralm has been used as Hochalm (alpine pasture used during the summer months) where the cattle were grazing during a short summer period from late June to mid-August. The way up to Angeralm was onerous for the animals and the dairymen, with craggy rocks wounding the animals’ hooves. It could also be dangerous too, due to the dolines and sink holes in the karst. The area has not been used for cattle grazing since 1897 and today the area around Angeralm is abandoned, with only a very small number of sheep remaining. As a result this area has regained its naturalness.

When we arrived at Angeralm we could see mount Angerkogel, the place where we hoped to find Crepis terglouensis. It is a rounded ridge, only 2114 m high, that rises about 200 m from the Angeralm-plateau.

Typically these exposed mountain tops in the karst are covered by short grassland species like Seslerion coeruleae. At this site we found several species from our target list: Pedicularis rosea, a species that grows in calcareous rocky grassland; Tofieldia pusilla and Homogyne discolor, common here but also be found in snowbed communities; Kobresia simpliciuscula, usually found in fens in alpine regions but also in this kind of grassland. The short grown alpine meadows are riddled with calcareous screes and rocks where specialized species can grow. This is the habitat of Crepis terglouensis. In the northern calcareous Alps this species is not rare and we found a lot of sterile rosettes in most of these open scree fields, but there were only a few individuals flowering and one or two fruiting.

Petrocallis pyrenaica, a tiny, pink flowering Brassicaceae formed cute cushions on the scree. Another Festuca species gained our attention. A small one, with a fine leaf blade – but there were three Festuca species with these attributes: Festuca pumila; Festuca alpina and Festuca rupicaprina. All three species look quite similar so you need a good lens to see the differences! That means every single individual has to be checked! This is time-consuming, and it was already late in the afternoon. As we are driving back to Graz today we decided not to collect Festuca now. However, we were able to collect Kobresia simpliciuscula as the population was large enough, and seed maturity was optimal.

On our way back to the car park we complete the collections we started on the ascent. In total we have been able to collect 5 species today and have found another beautiful collecting site. I will visit this place again in a few weeks to collect species that are currently flowering.

On the way down Dietmar told us that behind the Styrian border to Upper Austria tourism companies and politicians have plans for a ski-tunnel through mount Warscheneck to exploit a valley that is currently protected and untouched. A project like this would destroy the special landscape that supplies habitats for a variety of rare and endemic plant and animal species. The region of Totes Gebirge is one of the most secluded, lonely and natural places in our country! In our opinion there are already enough ski slopes.